Cheers to my fellow DDC—Dead Dads Club—the dreaded Father’s Day is here again. Grief is such a sticky, strange feeling. Some days, it feels like yesterday I was driving my dad around in his car for the last time; other days, he feels like he belongs to a lifetime ago. Some days, I ache to hug him and ask a million questions I never got the chance to ask. And yet, I am reminded of how lucky I was to have seventeen years with my dad, and the years I continue to share with my mother.

One in eight children—8.7 million kids aged 17 or younger—live in a household where at least one parent struggles with a substance use disorder (NSDUHs, 2014). Growing up in such an environment shapes a child’s limbic system, stress responses, beliefs, and morals. As adults, it becomes our responsibility to unlearn destructive behaviors, develop healthy coping skills, and allow ourselves to be vulnerable—to truly heal.

It took me years of reflection and work to understand how my dad’s alcoholism and his loss shaped me, both painfully and profoundly. For context, my dad had been in a car accident at nineteen. Both he and his father required blood transfusions, which resulted in contracting hepatitis C. His drinking had begun even before the accident.

Growing up, I could sense that some of my dad’s behaviors weren’t “normal” compared to other dads, but I didn’t realize he was battling addiction. I would wait until I heard him come home to sleep. I took off his shoes when he passed out on the couch. I’d put my finger under his nose to make sure he was breathing. Completely normal kid behaviors, I now understand. I even grew to love his scent—the mixture of grass, sweat, and booze.

We watched ‘Seinfeld’ on a tiny five-inch screen during dinner. We took annual spring break trips to visit family in Florida. We fought sometimes, yes, and as the years passed, the fights grew more intense, but we had what we needed. We traveled across the country in our RV—thanks to my geologist mom—and I thought my childhood was normal.

Everything changed in seventh grade, in 2001. My dad frequently went on “trips,” but this time, he left with all his belongings for what he called “China.” That day, he told me he didn’t know when he’d be back. I watched him drive away and cried in my room for days, silently, because I didn’t want anyone to know.

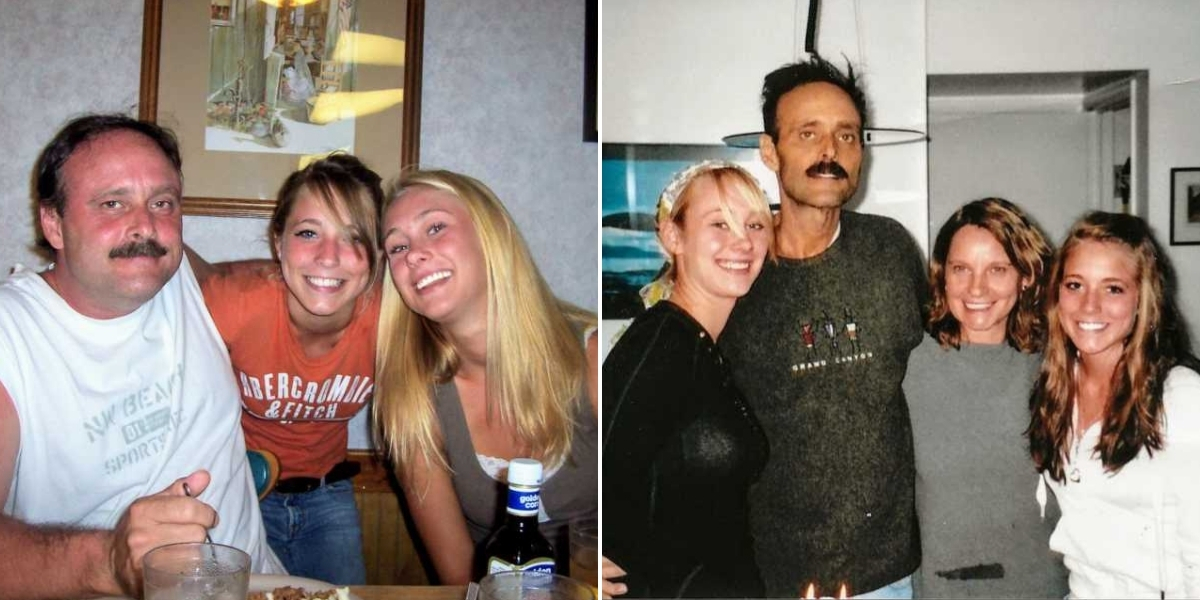

Divorced life became our new normal. My favorite days were the little surprises—my dad showing up at school or the bus stop with treats, driving my friends and me wherever we wanted. But in the fall of 2004, everything shifted again. My parents sat us down at the old creaky antique table to tell us the news. I remember my dad’s blotchy red face, explaining that his hepatitis C had led to liver cancer. My eyes filled with tears, but I held them back until I could leave the table. Denial set in as he began chemo and radiation, and life carried on as if nothing had changed.

Spring break 2006 was another Florida trip. We rented a boat, laughed, and had fun—but I noticed the sadness in my aunt’s eyes. That trip became my first real glimpse at the impending goodbye. Dad didn’t smile the same anymore, and on the last night, I saw tears in his eyes. “I’m still proud of you,” he said. “Everyone makes mistakes. I love you so much.” I hugged him, but my throat was tight, my words stuck. Regret.

Afterward, my parents remarried so my mom could care for him and secure his pension and life insurance. It wasn’t a dramatic move—it was love, friendship, and devotion. She took care of a man who had been an addict, who had cheated and gambled. She was, and still is, an angel. On his last Father’s Day, his yellowing eyes pierced through the door. I set my journal down and said, “I’m so sorry. I can’t do this anymore, Chelsea.” His use of my full name carved itself into me—a moment of vulnerable love I’ll never forget.

I’ll never forget the long hug that day, or the words I couldn’t fully express. I prayed silently for more years with him, just as he had hoped. When he finally left, I cried so hard I vomited—the first of many messy moments of grief. To see my once strong, 225-pound dad diminished, in pain, letting go—it was unbearable. That June was hard, yes, but also profoundly beautiful, naïve as I was to think there would be more Father’s Days to come.

The months that followed were a blur of sickness and love. My dad held on through pain, through depression and bargaining. In August, my grandpa fell from weakness, and I saw my dad cry inconsolably for the first time. He was never the same afterward. I wasn’t the same either.

We took one last family trip—to Las Vegas, the Hoover Dam, the Grand Canyon. Most of it was in a wheelchair, most smiles were quiet, but I could feel his contentment. I held, helped, and hugged him every chance I got. His last birthday, in late September, brought friends and family from far and wide. I barely ate. I cried so hard, I vomited again.

His final month was excruciating. I tried to be a happy high school senior while my world crumbled. My mother slept on cushions next to his hospice bed, caring for him tirelessly. I helped him with pain medication, bathroom needs, and simply being there when he asked. My homecoming weekend was his last. The last time he touched my face and held my hand, he said, “You’re so beautiful. I’m so sorry, Chelsea. I love you.” I ran upstairs, sobbing, learning for the first time how to pretend to be okay without a father at home.

On October 9, he entered hospice. I kept telling myself it was just a hospital visit, but the phone call on Wednesday morning told the truth. We didn’t truly say goodbye. After the funeral, I couldn’t cry for a month. I went through my senior year numb, traumatized, carrying disenfranchised grief. I left for college ten months later, feeling utterly lost.

College was a blur of parties, lost sleep, and poor grades. I tried to ignore my grief, believing it would fade with time. I avoided talking about my dad, omitting the truth because grief makes others uncomfortable. But slowly, I began to understand it—grief isn’t always heavy; it can exist quietly, like a shadow. I went to grad school, studied trauma, adult children of alcoholics, and adverse childhood experiences. I sought counseling. I learned about delayed and disenfranchised grief, about the importance of naming and feeling pain, about reclaiming love through memory.

If a loved one is sick, reach out. Talk about them. To grieve is to have loved deeply. Whether it’s been two months, two years, or twenty years, keep asking about the people you’ve lost. They may not be with us physically, but they live on in memory, in love, in us.