“‘Hey, look! It’s Two-Face from Batman!’ I can still hear the kids yelling that as I ran up to school that morning, my little heart pounding.

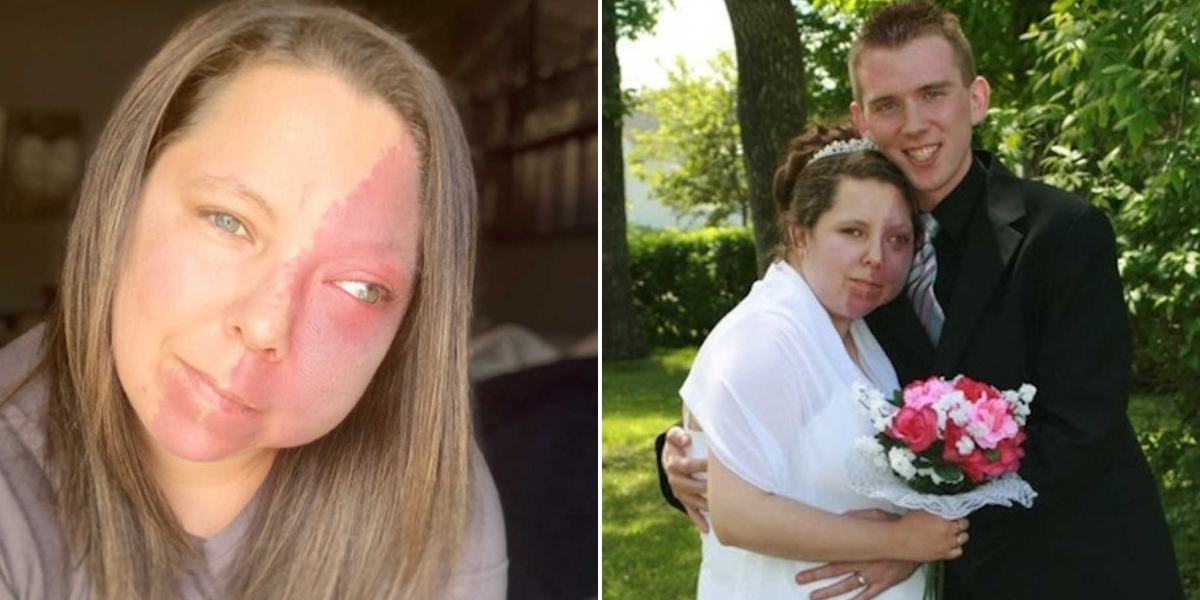

I was born with a rare neurological condition called Sturge-Weber Syndrome. On the left side of my head, I have a large port-wine stain birthmark. What most people don’t realize is that it’s not just a birthmark—it’s a sign of a much more complex condition. Depending on its location, Sturge-Weber Syndrome can bring many serious complications, and in my case, it came with challenges my parents never imagined.

The hardest part for them wasn’t the medical care—it was the staring, the whispers, the constant questions. My mother remembers people asking if I had been burned. She even recalls a man in the grocery store asking if she needed help escaping an abusive relationship because of her baby’s “bruise.” From her, I learned patience and kindness; she would calmly explain my condition, always with grace. Over time, everyone in our neighborhood knew Chelsey and her birthmark.

The medical complications grew more severe as I started having seizures around the age of one. They began as small jerks but quickly escalated to full grand mal episodes, during which I would be thrown backward, banging my head and flailing on the floor. Every available medication was tried—even some not yet approved in Canada, sent all the way from the United States. Despite these efforts, my health declined rapidly. My brain was calcifying, the seizures were relentless, and fevers and infections pushed my tiny body to its limits. Doctors began preparing my parents for the worst. I lay lethargic, almost unrecognizable in my hospital bed, and it seemed like hope was slipping away.

Then, a lifeline appeared. I was flown to the SickKids Hospital in Toronto for life-saving brain surgery at just 18 months old. After extensive testing and imaging, the surgical team pinpointed the exact malfunctioning area. The procedure, a six-hour operation, had only been performed once before at that hospital. They removed the problematic portion of my brain. My parents say walking past me in recovery was surreal—I was covered in tubes and bandages, bloodied, my birthmark hidden entirely. I was unrecognizable.

Recovery was intense. I had to relearn everything—walking, talking, even basic coordination. But within days, I was already singing and clapping along to songs. I emerged seizure-free and off medication, a miracle in the eyes of doctors. Statistically, I shouldn’t have survived; if I had, I likely wouldn’t have had the cognitive abilities I now enjoy.

School brought its own challenges. At first, classmates were frightened of me. I, in turn, was nervous about going. But thanks to kind, patient teachers, I was never excluded. Over the years, I made friends and learned to educate and advocate. I answered questions, smiled through stares, and slowly became comfortable in my own skin.

One unforgettable moment came with the release of a superhero movie. Watching the villain reveal an acid-burned face that looked just like mine, I knew life would change. The next day, bullies found me, chanted, and called me “Two-Face.”

At the same time, I was undergoing laser treatments for my birthmark. Starting at age four, the procedures were traumatizing. Numbing creams didn’t help; the lasers burned tiny purple dots deep into my sensitive skin. I was often held down as I screamed in pain. My mother eventually let me decide whether to continue treatment, realizing the emotional toll was too high.

As I grew, I returned to laser therapy—but only with anesthetics at specialized clinics. I traveled to Boston’s Shriner’s Hospital for treatments until I was 21. Even then, the pain felt like something endured for others, not for myself. Eventually, I stepped away from lasers and covering up, embracing my appearance as it was.

Early adulthood brought struggles with depression, self-acceptance, and self-love. Society often portrays anyone who looks different as a villain or an outsider. I felt isolated, disconnected from peers obsessed with superficial conversations.

Then, I met my husband through a mutual friend. As our relationship deepened, I embarked on true self-discovery. I learned to accept compliments, to recognize my own beauty, and to advocate for my rare condition with confidence.

Now, as a mother of two, I strive to show the world life through the eyes of someone with a facial difference. We are not monsters or villains, as media and social norms might suggest. I am thrilled when I see others embracing their differences, owning them, and teaching the world to accept and love diversity.

For several years, I have served as an ambassador for organizations supporting individuals with birthmarks and facial differences. I aim to be the support I once needed, to help others navigate their own journeys. Our scars—physical or emotional—are marks of true resilience. Half the battle is learning to see the beauty and strength in what makes us unique. We are incredible beings, and the world needs to understand that we don’t all have to look the same to succeed, to love, or to thrive.”